This is a newspaper column I wrote in the summer of 2014 when this issue of Southern heritage and Confederate flags and statues was raised. Yes, it comes up every so often and has for the past 120 years — about the time the urge to put up Confederate statues began long after the Civil War ended, oddly enough.

When the column was first published, a few didn’t really understand it and tried to be thoughtful and give me the details of my great-great grandfather’s service with the army of the Confederate States of America. They read right through my general lack of interest in the subject then — and now. Sadly, this is being debated again today, after a deadly incident in Charlottesville, Va. stemming in part from a rally to protect the statue of a Confederate general. That’s the problem with Civil War symbols, they mean different things to different people who have strong emotional feelings for or against them. This will not change, probably ever.

My position also remains largely the same today as it was then. The Civil War is a tragic part of American history and the monuments telling the story or remembering those who died do have a place in the proper context. Museums or memorial parks — like the one in Jacksonville, NC — serve as appropriate venues for such displays honoring war efforts and war dead, especially Civil War dead. They certainly do not belong at government centers. Centers of government aren’t really places for such memorials or monuments even if they’re not incredibly divisive. Government centers are places where all members of the public should feel welcome. No one should feel threatened. A symbol of our sad history of slavery should not be there.

Statues of military generals — or even statues of historic figures in general — should be placed in public sites only after serious thought. Too many times we learn after the fact that the people being honored aren’t worthy. In my view statues should really only be placed in the hometowns of the people being honored or some site where those persons made an incredible and positive mark on history or culture.

On the other hand, I also believe it’s wrong for people to go onto public property and take down these statues on their own. It’s vandalism and destruction of public property. There is a way for such actions to be discussed, debated and taken — or not. Those measures should be undertaken, not vandalism.

For an additional view by the ancestors of a Confederate veteran here’s a link to a letter written by the relatives of Gen. Stonewall Jackson.

So here’s the column about my thoughts on Southern heritage as the son of a son of a son of a Confederate veteran. Peace, folks. And in terms of an update, the kind folks I mentioned before provided me with information about my great-great grandfather’s service. He was overtaken by sickness and sent home just before Gettysburg where he might not have survived, meaning …

—

My great-great grandfather fought in the Civil War. Well, fought could be too strong a word to describe it. There’s no way to know for sure. In fact, I have little to no idea at all what, if any, action he might have seen. I only know he returned home to Danbury, North Carolina in one piece. More than 250,000 men from other communities didn’t do the same.

So that’s something.

Otherwise, there is no rich history of family stories about the exploits of Capt. Spotswood B. Taylor of North Carolina’s 53rd Infantry. Diaries, letters or even an oral tradition are non-existent. War stories of heroism, cowardice, tragedy or melancholy are lost to time. I have no idea where he traveled, whom he served with, or when or where he engaged in battle with his fellow Americans.

Yes, fellow Americans. That’s the harsh reality.

A few stray artifacts from that time are scattered among family members. There’s a sword and scabbard, for example. The last time I looked at it closely had to be 40 years ago at least. I remember it has CSA forged into the handle. There’s a portrait of the young captain — a harsh-looking fellow — in uniform. As a child, I recall being a little cowed by that portrait. The eyes — they pierced like the point of that old sword and seemed to follow me everywhere.

I think everyone knows the feeling.

There isn’t one clue in those items what motivated him to join the war or whether he was conscripted into the fight by the Confederate government. My hunch is that, as an officer, he signed the dotted line of his own accord. But his politics remain a mystery. I only know he was in the war, and that’s pretty much it.

BY DEFINITION this makes me the son of a Confederate veteran, or at least the son of a son of a son of a Confederate veteran. I suppose — also by definition — that would make the Civil War part of my heritage. This heritage thing is something I hear a lot about lately, as most are aware. So, yes, it’s part of my heritage. I have doubts that it’s really much in the way of direct heritage for some of the most vocal people in that group of Confederate flag-wavers these days.

Whatever.

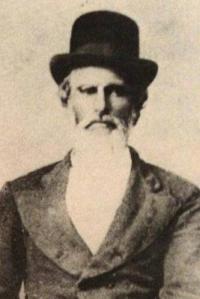

My great-great grandfather years after his service with the Confederacy in the Civil War.

Funny thing is I never consider it as part of my heritage when I consider it at all. The service of Capt. Spotswood B. Taylor of Danbury in the North Carolina 53rd Infantry isn’t something I’m particularly proud of from my family’s history, nor is it something I’m particularly ashamed of. It’s something I consider so infrequently that it usually ceases to exist in my mind. It’s a part of my family history from a war that ended 150 years ago. By the same token, one of my grandfathers served in World War I. I had an uncle seriously wounded in the Pacific during World War II.

On the former Courthouse Square in Danbury, there are monuments to Confederate dead and World War I dead. Interestingly, the Confederate monument is the most recent, and by decades. It was dedicated in 1990, not long after a new government center was built and the old Courthouse vacated of judges, lawyers, clerks of court and registrars of deeds. The World War I monument, on the other hand, was smack dab in the middle of the square, where I used to play hide and seek as a boy growing up in the 1960s.

I visit neither when I return to Danbury to see my family. At the base of my mom’s driveway fly the U.S. flag and the North Carolina state flag.

There are no others.

AFTER THE war, Capt. Spotswood B. Taylor of North Carolina’s 53rd Infantry returned home and operated a hotel and managed a vast amount of untamed land on a mountainside, a place that is now largely Hanging Rock State Park. His son, my great-grandfather, turned much of it into farmland. Hundreds of acres of tobacco were grown there after the Civil War, on land my family owned that was worked by tenant farmers. It was a better system than slavery, but that’s not saying a whole lot.

Did my great-great-grandfather own slaves? I haven’t the foggiest. It was never brought up even once by anyone in my presence. He didn’t own a plantation, and the land under his hand was too unwieldy for agriculture until his son took it over. But as a hotel owner, it wouldn’t be out of the question for that time. Slaves worked inside homes and businesses for white owners.

When I consider this, I fervently hope not. I would never want that as part of my Southern heritage. That is indeed something to be ashamed of. At this point, I’d rather not know at all.

That’s the tricky thing about an addiction to heritage. It delivers good, evil and all things in-between. Accept none of it, or accept all of it — and try to live with it. “Try” being the operative word.

The War Between the States continues to define generations of people here in the South, white and black. The world would be a better place if this were not so.

I wish more folks could celebrate Southern heritage the way I like to: Sitting outdoors on a summer night, watching lightnin’ bugs and sniffing honeysuckle. Maybe have a dish of banana pudding or homemade ice cream.

That’s heritage we can all live with.

Madison,

the current confederate Memorial on the Courthouse square in Danbury is the second one. The first was a cannon and a stack of cannon balls on a concrete slab on the opposite side of the Walkway into the Courthouse. Both it and the First World War Memorial, A doughboy with a rifle were contributed to the WWII scrap metal drive in early 1942 after Pearl Harbor.

LikeLike

Thanks. That’s good information to have.

LikeLike

Pingback: The disturbing disconnect of a county politician | Madison's Avenue

Pingback: Words and ideas from elected leaders really do matter | Madison's Avenue

Pingback: Silencing Sam | Madison's Avenue

Pingback: Family histories, unwanted surprises, and don’t call me Meredith | Madison's Avenue