This happened in 2006, on Nov. 22, the day before Thanksgiving that year. I wrote about the experience for the Jacksonville Daily News a couple of months later in January 2007. Five months after that, we moved to Burlington — that was a lot of stuff going on all at one short period of time. I haven’t shared this story for a while — the Daily News web site no longer has it (corporate malfeasance at work there). But I found a version the other day so I thought I would drag it out for the first time since 2013. It’s a reminder of how quickly things can go sour and also of how many thanks I still have for pretty much a full recovery. Every Thanksgiving I think about what happened. It’s also a reminder of what a great writer my wife Roselee is. Her journal entries make this piece so special.

—

Some mistakes I guess we never stop paying for.” The words played in my head in what seemed a continuous loop. I couldn’t hear much of anything else, at least not clearly. There were other things said that day in what would be my temporary room at Carteret General Hospital. But after awhile, this was all that came through:

“Some mistakes I guess we never stop paying for.”

I knew the origin of that line because I’d heard it many times. I was a film major in college and a baseball lover by rite of uncommon passion. The voice belonged to actor Robert Redford and it was from the movie “The Natural.” It’s the one where he portrays fictional and aging baseball star Roy Hobbs. I could even picture Redford as Bernard Malamoud’s tragic hero as he sat up in a hospital bed as the movie nears its end.

It was no coincidence that I was now doing the same.

“Some mistakes I guess we never stop paying for,” Redford, as Hobbs, said with resignation and a touch of fatalism as he recalled his downfall, which can be traced to a youthful indiscretion many years in the past. It was an action with consequences for Hobbs’ past, present and future. The bill for it kept coming around for payment — and always at the worst possible times. It’s a weary voice that says, “This is what it is.”

It’s what I’m thinking, too.

The day is Friday, Nov. 24, 2006, one day after Thanksgiving. I arrived at Carteret General at midday Wednesday, the morning my world changed, probably forever. Until this happened, I considered myself 47 years old and in reasonably good health.

Apparently I thought wrong. The tube in my chest on Friday — not to mention my shallow breathing — told me so. The tube was attached to what looked like a new garden hose, which led to a contraption on the floor by the bed that I called the “gurgling box.” It’s affixed to a machine on the wall of my hospital room.

This gurgling box followed me with the faith and loyalty of a good dog since I became tethered to it in the emergency room on Wednesday. It’s supposed to be making me better.

It’s not.

That’s what my doctor is telling me on this Friday, Nov. 24, the day after Thanksgiving. Dr. Bradford Drury warned this was a possibility when he met earlier in the week with my wife and me to lay out the scenarios for someone in my condition, for someone with something known as a “spontaneous pneumothorax.”

I’d be lying if I said I’d ever heard of it before. But, in short, my lung collapsed suddenly and for no outwardly apparent reason. Such things happen, I learned.

Who knew?

What Dr. Drury is telling me now is that the gurgling box won’t be able to do its job without some serious help. I was going to need surgery to repair some holes in my left lung, an organ turned to Swiss cheese by years of abuse administered by my own hand. What the doctor is trying to tell me is that I wouldn’t be in this shape today had I heeded the rather plain words attributed to the Surgeon General on each pack of cigarettes since the late 1960s.

Had I done so, I could have avoided 26 years of pasting my lungs with tar and nicotine. I put cigarettes away for good on May 1, 2002, but it was too late.

“…. caused by smoking,” Dr. Drury is telling me, his voice finding purchase in my mind above the painkillers prescribed to get me through the day. “Even though you quit smoking some time ago, the damage had been done.”

“Some mistakes I guess we never stop paying for,” I thought to myself.

Nov. 22, 2006: ‘Next time, call 911’

I thought I was having a heart attack. Actually that was my second guess. At first I thought it was a simple — but rather painful — muscle spasm in my left upper back. It felt like something exploded there. In a way, it had.

“Great,” I said to myself, anticipating the afternoon I had planned of working for my father-in-law doing what we always do on the day before Thanksgiving, set up our annual holiday business. “I was supposed to move Christmas trees today.”

But when the pain moved to my left chest and breathing became close to impossible I was absolutely certain of one thing: Heart attack for sure. It seemed unlikely I’d be moving any Christmas trees soon.

“You’ll do about anything to get out of a little manual labor,” my brother would joke later. From my perspective, he hit a little too close to the truth for me to correct him with any real conviction. I was at home by myself when it happened. This is how my wife, Roselee Papandrea Taylor, a reporter here at The Daily News, described it in the first of many e-mails she sent to our friends. Her messages became a de facto journal of what was happening to us. This one went out after 11 p.m. on Nov. 24.

“On Wednesday, Madison was off from work because he planned to help my father pick up Christmas trees. After he got up that morning, he sat down on the recliner to drink coffee and felt something in his left shoulder blade. It was painful. He thought he pulled a muscle. The pain quickly traveled to his chest and he became short of breath. …

“He got in his car and drove himself … to Eastern Carolina Internal Medicine, an urgent care clinic in the area. He figured if it was his back, he’d get some medication and still make it to the tree lot later. If it was his heart, he was at least in a medical facility.

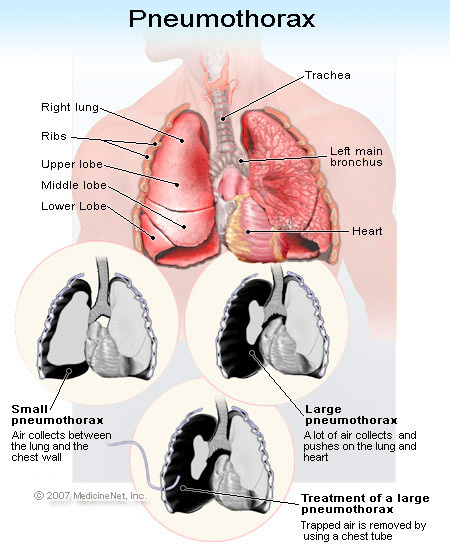

“It wasn’t either. His left lung collapsed — a result of a spontaneous pneumothorax. It’s something that usually happens in younger men, although long-term smokers can also be victims of it. Basically, there’s this thing called a bleb — an air pocket — that pops and the lung collapses and you can’t breathe very well.

“Madison smoked for 26 years even though he quit more than four years ago. …”

Eastern Carolina Internal Medicine is less than two miles from our house in Cape Carteret. I probably looked pretty pitiful when I shuffled in. A medical assistant asked if I needed to be seen right away.

“That might be a good idea,” I told her.

Later, Dr. James Regan, the physician who saw me that morning at ECIM, would tell me that he knew immediately what was going on. Fourteen years of experience in an emergency room made it fairly clear. He could detect a pneumothorax when he saw one.

“Textbook case,” he said.

On that morning, he listened to my chest and heard no movement at all in my left lung. He gave me a quick chest X-ray to be sure. “Do you smoke?” he asked.

“Not anymore but I was a heavy smoker for a long time,” I answered.

He shook his head knowingly.

“Your lung collapsed,” he said and explained to me what would happen next, that a trip to the hospital was in the cards. He tossed out a word I’d never heard before, “blebs.” It was a term I’d learn more about in the days to come. He told me later that my condition at the time was life-threatening. My lung had collapsed to the point where it could impede my heart.

“Did anybody ever tell you that?” he asked when I saw him weeks later.

They had not. Dr. Regan himself gave me lots of positives on that Wednesday.

“In 98 percent of cases like this, things come out just fine,” he said as the staff telephoned my wife and I tried to ease the fear I knew would be inevitable.

In the meantime, Dr. Regan tried to allay my apprehension. “No need to worry, but we’re calling an ambulance to take you to the hospital,” he told me.

Oddly enough, I felt fairly calm.

Collapsed lung? I’d never considered it as an option. When I heard it, I was actually relieved. Even though I’d never heard of a collapsed lung occurring to people who hadn’t been in a wreck or some other serious physical situation, I was pretty sure it could be fixed. It’s good that I didn’t know about that life-threatening thing.

At least it wasn’t a heart attack, I reasoned.

When the ambulance came to pick me up at ECIM, I was able to walk out on my own. As I looked back, Dr. Regan and the staff waved bon voyage like I was a cousin heading off for a cruise.

“Next time call 911,” Dr. Regan said with a smile as I walked toward the ambulance

In good hands

The next few hours are a blur when I think back now. I was asleep, of course, for much of it. The emergency room staff at Carteret General put me out so Dr. John Johnson of Carteret Surgical Associates could insert a chest tube. The tube goes through the chest wall. It is connected to a valve that lets the air escape from the chest cavity but doesn’t let any air back in. Once the air is removed, the lung can theoretically re-expand.

This is where the gurgling box comes in.

Dr. Johnson laid this all out before he started the procedure. He told me in most cases, the lung re-expands and reseals with no problem. If that doesn’t happen, well, there are other options. I didn’t like the sound of any of them.

I set my sights on the first scenario, hoped to get out of the hospital by Friday night and perhaps have a late Thanksgiving dinner by Saturday with family and friends who had come in from Ohio to spend the holiday with us.

Dr. Johnson also told me something else. He said the surgeon on call for the holiday weekend would be Dr. Bradford Drury also of Carteret Surgical Associates. I didn’t know then that he’s considered one of the top chest surgeons around.

“You’ll be in good hands,” Dr. Johnson said.

I would need to be.

This is how Roselee explained it in her journal.

“They put a chest tube in to reinflate the lung and expected it do the trick in 24 to 48 hours. Once the lung reinflated, the doctors also expected the hole to reseal itself.

“It didn’t happen.

“Tomorrow morning (Saturday) a surgeon will perform thoracoscopic pleurodesis on Madison to patch up the lung, reinflate it and make it all go away. In English, he goes under the knife and the doc fixes him using a scope. There’s a lot of pain and a morphine drip in Madison’s near future, but it should do the trick and prevent that lung from ever collapsing again. Thanks to a CT scan we know there are blebs in the right lung as well. They might bust spontaneously. They might not. The chance of reccurrence in the left lung would have been high, but the surgery should prevent that forever.”

Ugly in every way

When I look up the word “bleb” online this is what comes up:

“Bleb: A bladder-like structure more than 5 mm in diameter with thin walls that may be full of fluid. Also called a bulla.”

When I investigate further I also find this, “Spontaneous pneumothorax is caused by a rupture of a cyst or a small sac (bleb) on the surface of the lung.”

And Roselee, who was exposed to color photos of my lung, was more to the point in an e-mail she sent on Nov. 25, after my surgery was over she wrote, “Blebs are quite ugly … I don’t recommend them.”

I’ve never seen the images my wife was privy to, but I can add this: Blebs feel like hell, too.

Friday, Nov. 24: A quick study

Men and women are different. No big shock there. In our house I’m the one who wants the big picture. Roselee craves details. Dr. Bradford Drury was not only able but happy to supply both.

I saw Brad Drury for the first time on Thanksgiving Day and liked him right away. He was professional, to the point and had a dry sense of humor. He was confident. I like a confident surgeon.

Dr. Drury noticed then that the “gurgling box” didn’t seem to be doing the job and told me so. But he also said not to give up hope. He’d seen cases where the situation turned around. It wasn’t highly likely but not out of the realm of possibility, either.

I considered myself warned.

By Friday morning, he was less optimistic. That afternoon, he was ready to talk about those options Dr. Johnson mentioned.

Dr. Drury explained the thoracoscopic pleurodesis. It was a laparoscopic procedure in which three holes would be created on my side, “One for each hand and one for the camera,” he said. From that point, he spoke in highly technical terms. Roselee wanted to hear all of it. Me, I just wanted to know two things: Would I make it? And what would I be able to do afterward?

He assured me that I would make it, with the qualifier that all surgeries had inherent dangers. He also told me that I should eventually be able to do just about anything I do now when fully recovered.

“The exception would be scuba diving,” he said.

No problem. My ability to watch basketball on TV seemed safe.

Roselee, on the other hand, had plenty she still wanted to know, according to her journal on Nov. 24.

“Tonight I questioned his surgeon to death. I even pulled out a reporter’s notebook at one point. I asked if he had confidence in himself as a surgeon and wondered if he took pride in having a high success rate. He assured me with a smile that he was quite confident and his success rate was one that should make me proud.

“He’s won several medical awards — yes, I checked — did his surgical residency at Harvard’s Massachusetts General, spent several years practicing at … large hospitals in Raleigh before moving to Beaufort because he loves to sail.”

Drury also told us that while smoking might not have actually caused my condition, it likely played a starring role. And it was positively the reason more conventional treatment wouldn’t fix my problem. I was headed for a fairly substantial bit of surgery because I smoked for 26 years.

And that line from “The Natural“ began to play.

By this time the doctor was aware that we were newspaper people. He had a request, too.

“If you write about this, be sure to not only tell people to quit smoking, but let them know they should never start to begin with,” he said. “The damage starts with the first one.

“And tell people that lung cancer today is a disease of poverty,” he added. “The people impacted today are those without health insurance. Tell people that.”

I have a fairly strict policy in these matters: Never turn down a reasonable request from somebody who holds your life in their hands.

Nov. 25 2006: A day of complications

From Roselee’s journal:

“Madison’s surgery was originally going to take place midmorning, but it didn’t start until about 12:30 p.m. It was supposed to last 45 minutes.

“It took three hours. …

“… Needless to say, it was a rough three hours. I wore a hole in the waiting room floor. Madison had extensive bleb disease. (Whoever came up with the word bleb needs to be told a thing or two.) As a result of the whole bleb thing, the surgery was more complicated than anticipated. The good news is the outcome was exactly as the surgeon expected. The surgery was a success.

“They did put Madison in the critical care unit because it’s a holiday weekend and they want to be sure he’s getting monitored carefully. I was all for that, and it made it easier to leave when they kicked me out at 9 p.m. He should be back on the regular surgical floor tomorrow.

“ … Madison is in tremendous pain. Thank God for morphine and some other drug for nausea. The two mixed together knocked him straight into a good snore. He can only take shallow breaths, and it feels like the doctor is sitting on his chest. But he’s hanging in there. Thank you to everyone for your phone calls and e-mails. I really appreciate it, and I will pass on your warm wishes to Madison when he can actually retain who sent them.”

What she said.

A lost day

I had no clue about what was going on that Saturday until a day or so later. Had I known I was causing this much trouble I would have been worried sick — not for myself but for Roselee. No spouse should have to endure so much. I owe her big time.

For the most part, Saturday was a lost day. I remember waking up in CCU at one point and talking to Roselee. I was glad to see that the Rev. James Brown of First Missionary Baptist Church of Broadhurst Road in Jacksonville was there. He spoke to me at length and tried to keep the mood lively, but I had trouble focusing on what he was trying to say. Still, his broad shoulders were enough to support my family when needed. I won’t forget what he did for us that day.

Sunday was fuzzy, too. Morphine’ll do that. Nobody feels good the day after major surgery, but Roselee clearly thought I was getting better and I’ve learned to trust her judgment. At one point, I rose from the bed and took a seat in a chair nearby and we watched the last leg of “The Amazing Race” on TV. I couldn’t say now who won or lost, but it was encouraging to do something normal.

But things wouldn’t be normal again for several hours.

November 28, 2006: ‘Why is he getting sicker?’

From Roselee’s journal:

“I thought a lot about joy and sorrow today as it’s written in the book ‘The Prophet.’

“‘Your joy is your sorrow unmasked. And the selfsame well from which your laughter rises was oftentimes filled with your tears. And how else can it be? The deeper the sorrow carves into your being, the more joy you can contain.’

“After steadily progressing Sunday, Madison had a pretty major setback Monday. He didn’t sleep at all Sunday night in the critical care unit, his kidney function was poor, he developed a fever and a fast heartbeat and woke up extremely nauseous.

“The man I left Sunday night was not the person I returned to Monday morning. … Madison felt so bad that he could barely speak coherently.

“After asking the surgeon some pointed questions — mainly, ‘why is my husband getting sicker?’ — I sought refuge at a corner window in the CCU while the doctor pulled out the chest tube.

“The sun danced on the glistening water that was within my view, and I could see a pelican preening itself. It helped. I refused to give tears any opportunity to well.

“The doctor found me when he was done. The lung is sealed and filled with air. The tube is out. More deep breaths should discourage the fevers. He discontinued a pain medication that was impacting the kidneys and decided to put Madison on a progressive care unit … so he could continue to monitor his heartbeat. He also was willing to hear me out and did his best to alleviate my fears.

“Dr. Drury saw Madison four different times on Monday. I was grateful for the time but scared to death all the same.”

I’m getting better, honest

Our friends from Ohio had already returned home by Monday. But Brian Spurlock’s warning stayed with me. Brian, a former Navy corpsman at Camp Lejeune who is now in the Air Force, said that taking out the chest tube would be rather painful. I was in too bad a shape to notice.

That’s the blessing, I guess, in what Roselee put up with on Monday — when my condition briefly worsened. I was too sick to care that Dr. Drury was removing the tube. It was over in an instant. I barely knew it happened.

A couple of hours later, I was able to sit up in a chair in my new room on the progressive care wing. I was shaky but improving. My wife didn’t buy that, but I knew it just the same. My kidney and bowel functions were back in business. My fever was gone. I had turned the corner.

We had a short visit with our boss, Elliott Potter, who admired the sound-front view from my hospital room. He wondered aloud if it could be rented for July 4.

It was a pleasure to laugh, even a little. I told him I’d be back at work soon. He said not to worry.

So I didn’t.

Remarkable change

From Roselee’s journal:

“When I returned to the hospital Tuesday morning, Madison was a different person. He improved dramatically. It was such a relief. …

“… The change truly was that remarkable, and the nurses he has on the new unit have been so good to him. I am grateful. We had a really good day.

“… We will find out in the morning. There’s a good possibility he’ll be sent home tomorrow. If not, we expect it will be Thursday.”

Nov. 30 2006: Ready to go home

I didn’t go home on Wednesday. In hindsight, I probably wasn’t so much able as I was willing and ready. Roselee had to give me a “pep talk” to back down my disappointment. By the seventh day, I was ready to leave Carteret General. No offense to anybody there. The hospital did a magnificent job.

But nobody ever got stronger in the hospital. That’s what I was ready to do — get stronger.

The nurses took the morphine away, and for the first time in a week I wasn’t connected to some immovable object. I took the opportunity to walk up and down the hallway on my floor. I couldn’t move very fast and every so often there was a hitch in my breathing. After about 100 yards, I was dog tired and had to return to my room.

I would rest briefly then go out again. Roselee matched me step for step and watched me like a store detective staring down a potential shoplifter the whole time.

“Your husband is a determined man,” one of the nurses told my wife.

Dec. 1 2006: An early gift

From Roselee’s journal:

“He’s home.

“Dr. Drury, the surgeon, had several surgeries in the morning so we had to wait around the hospital for a few hours before Madison was released. It was such a relief when he gave him the OK. He was so kind to both of us and told us he really enjoyed getting to know us. I am very grateful the doctor on call during the long holiday weekend was the chest guy.

“On the way home from the hospital Madison asked if we could stop at my father’s house. My dad hasn’t been able to visit Madison while he was in the hospital because he’s selling Christmas trees from his house and doesn’t abandon ship once the season starts. He’s been extremely worried about Madison and was so thrilled to see him standing amid the Fraser firs today.”

We had a merry Christmas in a year in which our blessings could be counted in an abundance that seemed unthinkable a month before. I promised my wife that the new year would be better.

I intend to keep it.

Jan. 16 2007: The Natural thing

Roy Hobbs says something else in “The Natural.” I hear it in Robert Redford’s voice, too.

“You know I believe we have two lives. The life we learn with and the life we live with after that.”

I try to take that line to heart. I walk nearly every day now. It was hard at first. That initial 200 yards nearly left me breathless. But the next day I traveled 300 yards; the day after that a half mile. In 10 days I was doing nearly three miles.

Yesterday, I walked for more than an hour. That’s the target. Before the spontaneous pneumothorax I walked about twice a week.

Dr. Drury tells me that I’m recovering well from the collapsed lung and all it took to make it better. But I’m far from my normal self. After all, the condition that collapsed my left lung exists in the right. It could happen there anytime. It might not.

Those ugly blebs — they’ll haunt me the rest of my life.

Oddly enough, when I quit smoking in 2002, it wasn’t for health reasons. I just didn’t want to pay $20 for a carton of cigarettes anymore. And even though the damage had already been done, I’m glad I was well shed of cigarettes when this happened. I’d hate to deal with nicotine withdrawal with all that other stuff going on.

All things considered, it was a lesson I had to learn the hard way. I hope others out there are smarter. But the plain fact is, most of us aren’t. That’s just how it is. I’m not one to preach or anything. Folks should live the way they choose. I can say that I hope others learn from my mistake.

I have another appointment with Dr. Drury where he’ll inspect my scars and take an X-ray. Then he tells me I’ll need to see a lung specialist to guide me the rest of the way.

Whatever it takes to get better.

A Stokes story indeed. Tobacco gives on one hand for us and takes with the other. It paid my tuition and gave me opportunities in the wider world and stole years from most of my parents generation and made their older years a trial. The 300 years of tobacco agriculture gave our families a refuge from poverty in Northern Europe, but also inflicted chattel slavery which briefly yielded an economic bonanza for a few and a civil war for all. We are still in the reformation of our way of life as a result.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So true.

LikeLike